|

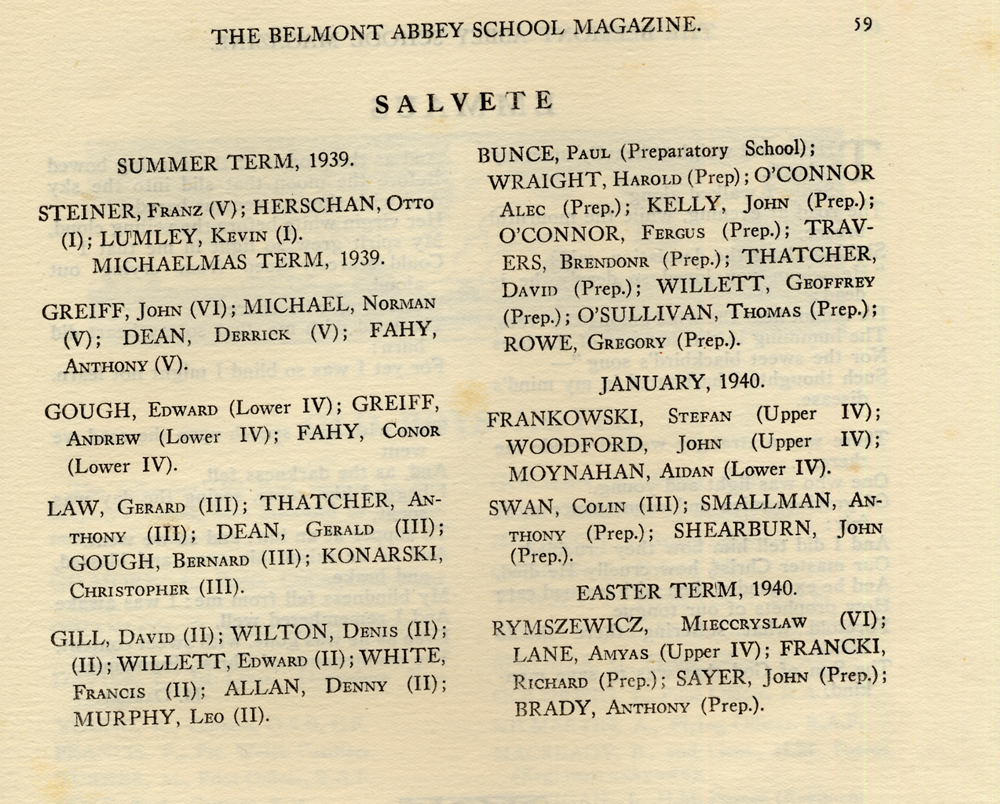

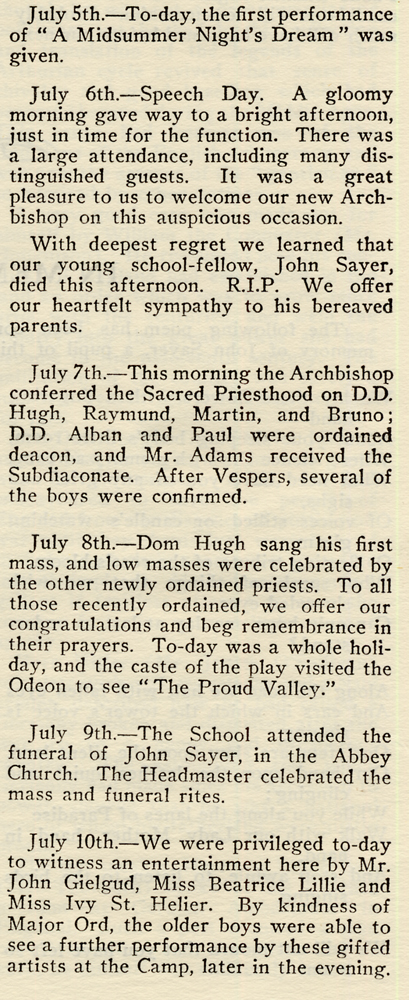

I cannot possibly compete with the encyclopaedic memory of my contemporary Geoff Garvey. However, I might just have a few recollections, which escaped him, so here goes… My father was a G.P.in Dulwich, and for the summer term 1939 my younger brother Fergus and I were taken from Honor Oak convent and sent to the near-idyllic St. Peter's School in Southbourne, Bournemouth. Jesuits ran this to senior level. The Junior House was most benign and with the sea nearby we had a great time. The sight of what we called the "Christchurch crocks" flying from the neighbouring aerodrome fed what turned out to be my lifelong passion for aviation. As the term ended we returned to London and a holiday on Exmoor, but with war clouds gathering our father must have made some rapid plans and on 1 September we found ourselves in the car heading for Belmont, where we joined several other boys. I can still remember standing on the grass outside the school buildings and hearing the words "We are at war with Germany". We spent an enjoyable few days before the start of term-time. We then formed the Junior House under the leadership of Brother Bruno Reynolds. In material terms life was quite hard, though in those pre-central heating days it was accepted, chilblains and all. There was no running hot water for our washbasins. Brother Bruno simply came round with a jug of hot water and gave each of us a small amount "to take the chill off". The food was variable in the extreme. At one stage relations between the community and the kitchen staff got so bad that frantic visits were made by Dom. Denis to the Ministry of Employment to prevent them walking out and it was rumoured that "kerosene had been put in the cheese pudding". This all underwent a magical transformation when Brother Bruno's sister took over. What had been happening to the supplies beforehand we will never know, but in the hands of "Miss Reynolds" we were very well looked after. That didn't stop us waiting to ambush the baker's van, where for a few pence a brown loaf could be bought and immediately consumed with a popular spread called "Betox" (a sort of jellified Marmite) or Fry's Chocolate Spread" Some of the domestic cleaning was done by a couple of ancient crones called Amy and Mamie. They always dressed completely in black and one day appeared at an impossibly early hour - half past three or four we were told. They apparently had no clock in there home and when told the real time were heard to say "It must have been the cawfee", this presumably being a luxury in which they rarely indulged! I turned out to be a bit if a "swot" and usually competed for first place with my friend Hal Wraight (What's happened to him, I often wonder). Games in the extremely cold winter weren't much fun but we all had to do them. There was a very popular informal game called "Cocker rosty" where one individual from a team tried to cross an open space defended by the other team. If successful he shouted "Cocker Rosty" and all his teammates tried to do the same. Whole holidays were known as "Floaters", presumably because in the past boys could go boating. Coach outings were sometimes arranged and I have particular memories of going to the pretty village of Weobley. The war seemed distant except for the constant presence of aeroplanes, mostly Proctors and Dominies from Madley. On one occasion a lumbering Whitley bomber flew very low over the school. Dom Denis said, "That must be Sproule", but I never found an R.A.F. or Belmont association with that name. There was a convent nearby where the Reverend Mother was a cousin of mine. I served Mass there for the very first time. Afterwards I was hugely embarrassed when the nuns produced as a breakfast treat two fried eggs. As a confirmed egg-hater I just had to refuse - a minor event today but in those days of shortages much more significant! The convent was on the road to Clehonger, where lay Ridlers Cider Works. The monks must have been very good at turning a blind eye to the fact that we often went there to buy bottles of cider (1/3d for ordinary, 1/9d for "champagne") and quaff it as we walked back to the school. Our other "vice" was smoking in the train home at the end of term. Again a blind eye was turned and we competed with brands such as Balkan Sobranie, Craven A, and the much more expensive oval Wills Passing Cloud. Perhaps that early experience resulted in my non-smoking life thereafter. We had one tragedy. Some boys caught Scarlet fever, a serious but rarely fatal illness. One, John Sayer, was taken to hospital, and on the day before Brother Bruno's ordination to the priesthood, which should have been a joyous event, Brother Bruno gathered us together for the announcement "John Sayer has died". This was particularly sad for John's best friend John Shearburn, who later made a big name for himself as a Chaplain in the Prison Service, which justified a full-page obituary in the Daily Telegraph. Sadly, I regained contact with John quite by chance a few years ago only a short while before his death from leukaemia. Our first headmaster was Father Christopher McNulty. He left after a while for chaplain service in the R.A.F. I saw in the Catholic Who's Who" many years later that he had been "laicised by permission of the Holy See" but I never discovered the story behind that. He died relatively young. His successor was Father Alphege Gleeson. The first Abbot was a formidable figure that always took snuff as he left the refectory. He may have had a sense of humour. A monk used to read at meals and one occasion the passage was all about a king (or nobleman of some sort) named "Clovis". And who should the selected reader be but Father Martin, whose nickname for some reason was "Clovey" . Needless to say much subdued chuckling could be heard around the refectory at every mention of "Clovis". Among the other staff I have vivid memories of "Arkey" Semple, a former cavalry and Royal Flying Corps Officer and fine musician who led the choir, where I sang treble, in a broadcast performance. Father Francis, who taught chemistry, was the oldest Benedictine in the English congregation when he died. Father Bernard Chambers was another more volatile ex-W.W.1 pilot who thought nothing of hurling a heavy blackboard rubber across the classroom at a boy who irritated him. Father Fabian Lee was an expert swimmer, reputedly of Olympic standard, who watched over us in the River Wye. Health and Safety certainly gave way to enjoyment and I remember two boys breaking limbs, one falling off a towed farm cart and another falling from a rope suspended from a tree near the river. Someone at Belmont must have had considerable clout in the entertainment world because we had a visit from a trio of entertainers who were even in those days household names. They were John (later Sir John) Geilgud, Wendy Hiller, and Jeanne de Casalis. They gave us a great evening show, though the only item I can now remember was Jeanne de Casalis having a comic telephone conversation about squeezing oranges! At the end of the summer term 1943 my brother and I said farewell to Belmont. He was off to St. George's Weybridge, and I went to Downside, from where we pursued careers in the regular army and the aviation world respectively. I was delighted to meet my contemporary Philip Thwaites when he started R.A.F flying training in Southern Rhodesia a couple of months after me, and Michael Rigby a few years later when he was flying Canberras at Binbrook in Lincolnshire. Many years later our son went to Llanarth, where we found Father Bruno Reynolds again. This was a great occasion and we had many chats about the old days. I have been very pleased to find the thriving Old Boys' Association and am most grateful for all the work put into the Website. I hope that these rather disjointed memories may add a little to the already comprehensive account of the early wartime years given by Geoff Garvey.

I

|