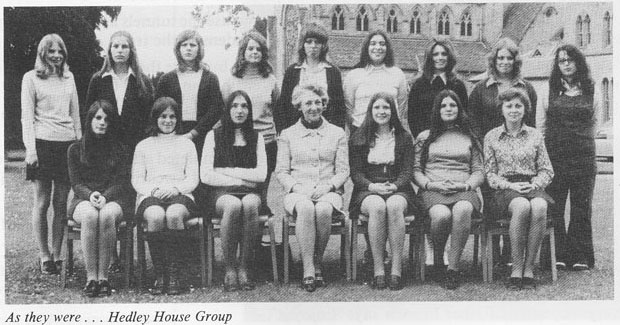

Hedley House was the boarding house for girls at Belmont from 1971-1978.

|

|

|

|

HEDLEY KALEIDOSCOPE by Pauline King, M.B.E., S.R.N. 1988.

When Michael Caswell asked me to write an article about Hedley House, kaleidoscopic impressions

formed in my mind, shifted, dissolved, re-formed — and I realised that I had a title. Belmont boys to

whom, for five years, I tried to teach English 'Lang. and Lit.' and whom I urged to use personal

dictionaries will, I hope, know that 'kaleidoscope' is made up of three Greek words:

kalos (beautiful)

eidos (form)

skopeo (look at),

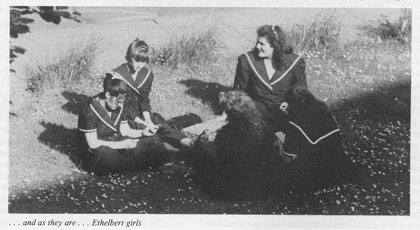

together summarising my first glimpse of eight beautiful Hedley girls strolling gracefully around a sunlit

campus under the admiring gaze of sixth form boys.

It was an April evening in 1971: I had been widowed for six months and was ready to accept the

challenge of taking on Hedley House for ONE term — as I supposed. Being already committed to

attending an International Ecumenical Conference I was excused the first two days of term because the

sixth formers were in retreat. I arrived as they finished and, having driven many miles, was still wearing

a trouser suit.

'Hullo! Can we wear trousers?' they greeted their new Housemistress.

'Why not?'

Eyeing their scanty mini-skirts I speculated that trousers might be less distracting for the boys. I was

wrong, of course.

When they got their new trouser suits some of the girls didn't like them: too like mine, I suppose. I had

old-fashioned ideas about provocation and had insisted that the tunic tops covered their posteriors;

some being larger than others.

TALENTS, AIMS AND AMBITIONS

It was naive of me to assume that all Belmont's girls would be dedicated to obtaining as good 'A Level'

grades as possible in order to ensure places at the universities, training colleges and professional

training establishments to which they aspired. Some were: some were not. But, throughout Hedley's

existence they acquitted themselves well in many fields and won a high proportion of academic and

sporting prizes at each Speech Day; as well as Headmaster's and other special ties, colours and

privileges.

The girls brought a wide range of talents with them: two were junior county tennis players, one was

awarded a place on a National Youth Theatre scheme, another was an expert with foil and rapier.

Belmont uncovered and developed further unsuspected gifts. Eleanor proved to be a naturally good

shot the first time she fired a rifle; her coach put up a second target and the same bull's eye was hit.

Others, trained by our coaches and the boys themselves, did amazingly well in the Hereford Junior

County Athletics championships. Hedley also competed against local girls' schools and won tennis,

basketball and badminton matches; played squash and golf, rode, and — through the determination of

Rose Rigby — persuaded Dom Mark Jabale to teach them how to row. I recall their first lesson in the

tank at the Hereford Rowing Club and, later, standing on windy riverbanks watching their progress.

Sometimes they could be fitted into the school buses with the boys: if not, my estate car was useful for

that as well as for ferrying rugby casualties (boys!) to hospital and taking Liberal Studies' groups to visit

Approved School, Cider Factory or other mind-blowing centres of education.

In getting the rowing under way, Rose was relentless in her assaults on the Top Table at lunch time:

'Are you going to coach us today. Father Mark?' The headmaster found it difficult to deny such

devotion to his chosen sport and he, Mr. Davis, and some boys, coached them. At their first regatta, the

Belmont Women's Four finished less than a length behind a University Women's crew that had rowed

together for three years.

The girls camped and trekked alongside the boys, through the Black Mountains and they were not

displeased when an Army officer told them that the trek they were engaged upon was more severe and

testing than he would allow his young soldiers to attempt. Only one girl had a minor sprained ankle: but

the master in charge decided that the girls must drop out of the Duke of Edinburgh scheme.

Their ambitions for the future included medicine, nursing, the law, teaching, writing, economics. Rose

planned to become a naval architect, others radiographers and physiotherapists. I privately forecast

that one would be a distinguished Reverend Mother General: but I was wrong — again! However,

several of the Old Girls are involved in catechetical work, or in other words further the Faith, so Belmont

has successfully supported the all-important HOME influence.

DRAMA AND DOMESTICITY

Initially the girls' House was split between two buildings separated by the school infirmary and

refectory block, the monks' garth and the Phillipps' Library. Four girls slept on the first floor of Siberia

under my supervision and the other four were in the custom-built Hedley House above the Head Boy's

Day Room and the school bookshop. Hedley was a designer's dream — amethyst carpets and curtains,

white painted brick and yellow wood. It was, if I may say so, expensively inadequate with tiny desks and

built in cupboards: attractive at first glance but impractical. The division of the House did not matter

during the summer but, in the hard winter of 1971 - 2, the midnight telephone calls from Matron,

advising me that the girls' lights were on and a party in progress, meant that I had to traverse a gallery,

descend the stairs, and let myself out into the ice, snow and rain, in order to reach Hedley's front door;

thence up another staircase — to read the riot act. There was a young maths mistress sleeping in the

house but she seemed not to wake! It did not occur to me to protest, but as it happened, the Abbot and

Headmaster decided that the two halves of Hedley must be brought together, by a transfer of the school

infirmary to Siberia, extended by rooms taken off the monastery. A new flat was built for matron and I

supplemented the furniture she had left behind in her former flat by providing some of my own,

including fridge, filing cabinet, chest of drawers, curtains and bedding.

I returned three days before term started to find that, although the workmen had disappeared, nothing

had been cleared up and there was no staff to do it: except myself. I collected twenty-eight dirty cups and

saucers, countless tools, screws and nails; swept up sawdust and cigarette ends and, allowing myself

only two hours' sleep, achieved a more or less clean house by the time the girl monitors returned. They

were delighted with the new house and joined me in making beds, sewing and hanging curtains for the

corner wardrobes, and in painting the whitewood chests of drawers which we had bought to save the

expense of built in furniture.

When the new girls and their parents arrived, Hedley looked as though it was ready although, in fact, far

from finished. I spent the next night and day plastering, wall-papering and painting. Someone told me

that the Headmaster had dined out on the story that his Housemistress was doing a decorator's job. I

wouldn't want to do it again but it was a challenge and fun, if somewhat exhausting. The senior girls

entered into it magnificenty and, somehow, a Benedictine tradition of hospitality was upheld.

Despite the extra study bedrooms we could not accomodate more than twenty-two boarders but the

steady request for places was confirmation of the need for a FAMILY boarding school where brothers

and sisters can be educated together — thus saving their parents endless manoeuvring and travelling at

half-term and on other occasions.

The girls contributed to the school's dramatic production as actresses, scene painters, costume makers

and — after two years — I persuaded them to enter for the inter-house concert contest. Before I arrived

at Belmont the first few girls, having bravely entered the competition, had endured harsh barracking, so

they were understandably reluctant to expose themselves to ridicule again. To encourage them, I

cheated by writing a script about a fashion show — with lots of in-jokes. Pleased with the idea, they

worked hard, on their own, to achieve a standard of acting and production that put them in second

place. The BBC adjudicator told me that he would have put them first but as he was a guest in a Boys'

House he did not dare: it might have strained hospitality too far. The following year the girls won and

the sight of them as they sang 'Milor' — dressed in top hats, spotless white shirts and bow ties, black

tights (for which we had scoured Hereford), shining black, high-heeled court shoes, and flaunting long

black cigarette holders, is one of my most vivid kaleidoscopic impressions. They brought down the

house, and in both 1975 and 1976, all the wolf whistles and cat calls were complimentary. The girls

surprised even their singing masters by the beautiful harmonies they achieved: 'Make me a Channel of

Your Peace', 'Where Have All the Flowers Gone?' and, finally 'Milor' with its dance routine, were some

of their conspicuous successes. There was a frank and healthy admiration expressed for the girls' good

looks of Angela, poured into a shiny black swim-suit, boys, staff and other girls commented, 'I'd no idea

she has such a super figure!' Critics sometimes exaggerate what was, in general, a very normal

atmosphere.

To celebrate their success in the inter-house contests the girls asked me if, following their party, I would

take them up to the rugby field: they would not sleep for excitement otherwise. There they sang in the

moonlight, their clear young voices carrying as far as the monastery. We were appalled to see lights

going on in the monks' cells but Abbot Jerome was most charitable when I apologised next day.

Hedley also excelled at more domestic occupations. It was nothing for us to be asked, especially during

the illness of Miss Crump, to help with the alterations to school uniform required for a new boy from a

distant country. The girls mended and sewed on name tapes for boys of all ages and not merely for the

lions of the First XV and the Cricket XI. Our ironing boards and drying rooms were frequenty piled

with shirts that some boy needed in a hurry. Sometimes it was a young boy who had been told that he

looked scruffy and was letting down his house.

The boys' houses had daily cleaners and, in addition, the junior boys acted as honorary servants

performing tasks that kept their respective houses looking clean and tidy. A sixth form girls' house has

no such corps of honorary servants and we had but a few hours help on two mornings a week (provided

that our Mrs. Fry was neither ill nor required elsewhere). The girls kept their own rooms clean and I

cleaned the bedsitter-cum-office that I occupied for my first four terms and, when we were moved to

our new quarters, cleaned, painted and partly furnished the former Matron's flat and kept that clean.

With a teaching programme and housemistress' duties to be fitted in, plus tutorials and extra-curricular

activities, there were no idle moments. I had no deputy (there were only twenty-two girls), but it was

a twenty-four hour day, seven days a week. On the occasion of a graduation, wedding or vow day of one

of my sons, a friend would sleep in. Once a fortnight I drove back to Bath for a few hours to pay

bills, see my gardener and housekeeper, and stock up the fridge and freezer for sons and a nephew living

at home.

It was accepted that the women in Hedley were capable and 'enjoyed' domestic chores so, when the

kitchen staff went on strike, the domestic bursar of those days came straight upstairs and asked me if the

girls would undertake the washing up for school, teaching staff and monastery.

"I'm sure they would," I said, "but they're here to get their 'A Levels'. I will do it and when they see me

through the grille, some may volunteer."

They did, and for two and a half days we performed all the kitchen washing up as well as keeping up with

our lectures, essays, teaching. Then I, metaphorically, blew the whistle and said 'Everybody out! It's the

boys' turn!' The strike was settled that afternoon.

I thought it might be useful if some of the boys learnt to cook in order that they might cope better with

life-after-school in bed-sits and flats and discovered that Hoime Lacy Agricultural College offered

courses. The headmaster encouraged me to make arrangements which, I believe, continue. No doubt

Brother William still ferries the cooks to and fro: my former boys' secretary is now a monk! Few girls

wanted to cook but the boys enjoyed supplementing their diets.

On one occasion Hedley took over the school infirmary for a week-end when matron had to attend a

silver wedding. There were five sick boys — most unusually — and the girls enjoyed it as much as I did. I

hasten to say that I am an SRN! Belmont expects professional staffing in its infirmary. When Matron

was out I also kept my hand in with boys taken ill or injured; the girls were rarely ill which was just as well;

there was a matron's rule, at one time, that excluded any girl from the infirmary if a boy was admitted.

Mercifully, we had only one epidemic affecting Hedley, an outbreak of 'flu in my last term, and the girls

were over it before I succumbed.

BELMONT/HEDLEY MARRIAGES AND A SHARED VOCABULARY

It is interesting to note that several marriages have taken place between Belmont Old Boys and Girls.

None, I hasten to add, was officially approved or blessed while the contracting parties were at school!

But how convenient it must be to share the Belmont vocabulary of the 1970s and thus be able to refer to

food as 'nosh' without creating a misunderstanding; to recognise, also, that 'Grease! Greased

accompanied by loud sucking noises, has nothing to do with blocked drains but implies that someone

with good manners is seeking to ingratiate himself with a superior.

Similarly, it could be useful to recall that "I have seen you socialising" contains the accusation that two

people of opposite sexes have been enjoying each other's company in the wrong place, at the wrong

time. Whereas the defence: "But we were only socialising!" accompanied by an injured expression,

indicates that the one accused considers it totally unreasonable for anyone (e.g. a husband/wife or

housemistress) to wish to be in bed before one o'clock in the morning (or even later should there be a

need for play rehersals). In Belmont/Hedley tensions the late start of a prayer group session, or of

scene-painting, followed by the URGENT necessity for a restorative coffee party, could become either

tiresome or fraught, depending upon whether one was the person waiting up into the small hours or the

victim of prejudice and mistrust.

Historically, in the case ofHedley, the crazy notion that Mrs. King had a duty to check and see that all

girls were in bed and the House locked up at a reasonable hour (whose 'reason'? Oh, these

grandmothers!) was one of Queenie's quaint fantasies. However it could be worthwhile for young

Belmont/Hedley parents to develop an early understanding with their off-spring that 'socialising' can

be both tiresome and injudicious. Otherwise they'll be in for an awful lot of late nights!

The word 'stroppy' meant that a member of staff had taken something amiss, was refusing a permission,

ruining one's life or insisting upon an essay being handed in. Imagine the Belmont/Hedley couple

accusing each other over the breakfast table, of being 'stroppy' or 'out socialising till the small hours' or

of 'skiving' when the washing up needed doing!

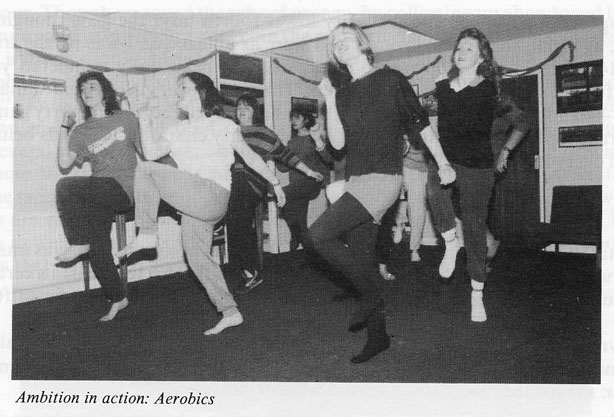

'Skiving' was the accusation commonly levelled, by a boy monitor, against a girl of non-athletic

disposition, who had refused to indulge in two periods a week of vigorous exercise — as required by

school regulations (Can't find it in the handbook but I know it existed: I used to feel sorry for the

defaulters when the weather was wet and windy). 'Skiving' could become an art. One of our Old Girls

completed her teacher training course and obtained her certificate without once taking part in the

compulsory P.E. ("Oh, SUE!")

My education in 'Belmont speak' came early in my first term when the Head Boy approached me after

Mass and asked me to punish a young lady who had sworn at a prefect.

'What — in the Abbey Church? During MASS?" I was convent-educated and easily scandalised. "What

did she say?"

The Head Boy blushed and looked down at his shoes.

"That's all right. I'll ask her," I said. I did; but the culprit also flushed and remained silent.

"If I'm supposed to punish you I must know what you've said."

She murmured the anglo-Saxon expression but I was none the wiser, despite having nursed British,

Colonial and A-merican servicemen throughout six years of war; so I feigned horror. "How perfectly

disgraceful! Go and wash down the wall in the common-room where the coffee has been splashed

around." Then I rang one of my lawyer sons and asked him what it meant.

"Good, Lord, Mother! You can't use words like that!"

The year was 1971: more recently I have heard the word on television: it still sounds what my Mother

would call "unnecessary".

PERMITS, PARTIES AND PROHIBITIONS

In my first term, I had the good fortune to spot something that had escaped the eye of the previous

housemistress. A monitor had forged her parent's signature on a smoking permit. It is useful to get a

reputation for omniscience even if it can't be sustained. It is also useful to be able to sew. Cathy

disapproved of the modest 'Seven inches from the floor when kneeling' which was the mark of decency

agreed between matron and my predecessor before I came on the scene: one measured it with a ruler as

the girl knelt on the floor. Very tedious. It was during study time on a Saturday that I came across a

mutilated dress at which Cathy had chopped with nail scissors. She had no other dress to wear at

Sunday Mass and, surprised by my own patience, I fished the wavy hem out of the wastepaper basket

and sat down to sew. It took me all Saturday and much of Sunday but, when I'd finished, no one would

have known that the lowest six inches had ever been divorced from the dress and I was spared the

reproaches of visiting parents, lay staff and monks, who not infrequently, took exception to the

extremes of fashion (fun-fur collars and pink plastic shoes for instance) and coats ofunsober hue, with

which a few girls liked to express their personalities.

It was a joy when we had parties and dances for which the girls could really dress-up and many of them

would wander into my flat to ask for comments or advice. It was like having a large family of daughters

or a house party for debs.

I acquired a reputation for prudish insensitivity after one of our earliest Hedley House parties. Three

girls failed to show up for morning prayers (a school rule) and I went along to see why they had

overslept. They declared themselves 'hung-over' and asked to be excused classes that day.

"Certainly NOT!" I exclaimed. "You must learn to carry your drink like GENTLEWOMEN!" Mrs.

Thatcher would have been proud of my Victorian values.

On another occasion the correct Victorian phrase rose equally easily to my lips. A young Old Boy, who

had been invited back to help with a trek, had been out on the Welsh mountains all day, and

had 'been

unable to see his girl friend of the previous summer. He took a chance, came up to Hedley after

midnight, and had slipped into her room for an entirely chaste visit, when (alerted by the slight sound of

a door closing) I appeared. I told him to apologise next morning to his host, the headmaster, for a

'breach of hospitality'! Before breakfast he was up to ask if I really meant it! "Most certainly, f do!"

And I went down and warned Dom Mark that he was on no account to laugh.

It was quickly realised that I wasn't a beer drinker and didn't know a barrel from a firkin. My menfolk

had always dealt with that sort of thing. When I suggested that a firkin would provide enough drink for

the boys coming to a party in Siberia, it was made clear to me that this would constitute parsimonious

hospitality; the guests would be dry, shocked and disappointed, our reputation in ruins. I agreed to the

barrel. I didn't see it taken upstairs but learnt that it required several rugby backs (and forwards) to lift

it. It certainly looked very large. The party went well and everyone appeared to have had enough —

(possibly too much?) to drink. The girls were, understandably, jubilant to have had a successful evening

and they told me they would spend the entire week-end clearing up: outside Mass and study time of

course. '

Greatly edified I waited for thirty-six hours before mounting the stairs to Siberia to inspect and to thank

them. To my surprise (it was my first year), a mixed party of equal numbers (forbidden by the

handbook) was in full swing and the clearing-up was minimal. It was a learning experience for me and

for them. The girls' parties acquired a reputation for originality and good food: they were carefully

planned and executed but I did find the fancy dress ones a little — devious. How can you pick out a

pirate wearing an eye-patch and a moustache and be absolutely sure he is not the fellow banned by his

Housemaster from attending any Hedley House parties whatsoever? Smuggled through a window

hiding behind friends and pillars — he's on a winning streak. But I did manage to see through his

disguise eventually and packed him off.

When I first proposed a party for about twenty lower fourth boys the girls thought it would be so

'BORING!' but, as usual, they rallied round and were as amazed as I was by the transformation of

scruffy 13 and 14 year old schoolboys into sleek, smooth, beautifully mannered young gentlemen

attired in colourful silk shirts and pressed trousers. The sixth-form girls — unattainable goddesses to

the lower school — sat on the floor on scatter cushions and played the kind of party games that families,

with a wide age range, play on Christmas night. It was utterly charming, the girls behaved like angelic

elder sisters, and everyone enjoyed it.

ATTITUDES

I was unaware that the decision to introduce girls at sixth-form boarding level was unsupported by full

consultation between the monastic community and the lay staff. This resulted in a certain ambivalence

on the part of adults and boys and is reflected in an essay handed to me by one of my fifteen year old boy

pupils:

"Women," he wrote, "are known to be of low intelligence and ability both physically and mentally.

They are weak and easily discouraged, unable to accept responsibility — or to lead." I never did meet his

mother or sisters: maybe they were too dim and weak to travel.

Another example occured one evening in the Martin building when, a master being delayed, his class

started a riot which prevented anyone in adjoining classrooms from studying. A sixth form girl, who

had been a monitor in her convent school, went along, quelled the riot and sent the ring-leader over to

his house. The boy was given a sweet and told that girls had no jurisdiction in Belmont.

I found these examples of male chauvinism surprising: why would an independent boys' school open its

doors to women and then regard them as second-class citizens?

Some girls earned admiration as much for their sense of adventure as for their charm. Gemma was a

qualified glider pilot and she and a sixth form boy, who had his pilot's A licence, were allowed to

practise their skills from a local aerodrome. One day they announced that they had his housemaster's

written permission to celebrate some Free Day or other by flying together. I checked and it was in order.

At supper time I congratulated the headmaster on his swinging school — mentioning that two of his

pupils had enjoyed themselves flying to Cardiff for lunch, Birmingham for tea and back to Hereford.

"They did WHAT?" he exclaimed. "Who gave them permission?"

"Didn't you?" I asked.

"Good grief! Suppose they'd been killed or maimed?"

I had an instant vision of a coroner, shocked and amazed, asking how I — a grandmother — could allow

such a venture. But then I thought, "No dammit! At their age my boyfriends were shooting other men

out of the sky and I was nursing the survivors. Perhaps my confidence was due to the fact that the girl's

father, a much decorated Colonel, was an old friend of my husband and myself. Later he confirmed that

he would have backed me whatever accident happened and, as he was a Rugby Blue AND an

International, I dare say that Belmont would have accepted his point of view.

Rugby was, of course, Belmont's great game. One afternoon a monk came up to Hedley to advise me

that the girls were disgracing Belmont by vulgar and vociferous support which was lowering the tone of

a blood-match against Llandovery. Conscious that anything that might adversely affect Belmont

Rugby was a mortal sin, and probably reserved to the Pope to absolve, I hurried in the wake of the monk

arriving on the field to see a diminutive South American jumping up and down, blue eyes blazing and

yellow curls bobbing as she yelled:

"Come ON, Belmont! Put the boot in! KILL him!"

"You see?" said the monk. "DISGUSTING!"

The pretty little cheer leader is now married and the mother of three children. I wonder if she teaches

them rugby songs?

It didn't seem to matter what the girls did, as far as some conservative die-hards were concerned, they

were in a no-win situation. Though they joined prayer groups, went often to Mass and had an almost

one hundred per cent attendance at the Hedley House Masses — they received no credit: women were

naturally religious. Though we saved the school money, by collecting up abandoned folding tables from

around the campus and using them as desks in the converted study bedrooms: though they painted the

House so that it always looked fresh (well, yes, some decorators weren't exactly volunteers but on

jankers); though they brought their own duvets from home and paid for their hair-dryers and T.V. —

the girls were "LIVING IN LUXURY"! We stopped painting the walls when we returned from a

summer holiday to find we had been re-decorated in sickly petunia pink. Though the girls were

secretaries of several school societies; on the editorial board of the magazine, conscientious volunteers

at the Blind Home, the Handicapped Children's Holiday and the Abbey Parish fete; taking their turn as

life-savers at the swimming bath, mopping up excesses during or after a party, they were still targets for

criticism. They are scattered now in Australia, France, Germany, Indonesia, the United States and

South America as well as in the United Kingdom and Ireland — but they laugh about the joyous and

irritating things that happened and remember Belmont with great affection.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CAREERS

The girls were all sixth formers but I taught boys from thirteen to eighteen — Divinity, Scripture,

English, Liberal Studies, Public Speaking and Debating. I was asked to set up a sixth form debating

society and they acquitted themselves well in the local, preliminary, and regional rounds of the Observer

Mace contest beating Clifton, Downside, Malvern, Millfield, Monmouth and many other famous

schools. I took the lower schook (Kemble Society) for debating and also trained our young teams for the

Rotary Public Speaking which, in those days, was a purely local effort. Each year we were awarded

prizes for either the best chairman, best speaker or best team, and were featured in the local press.

Before (and since) my years at Belmont I have lectured to what one might call 'consenting adults' on

such subjects as International Humanitarian Law, Emergency Relief work and Ecumenism, so taking

on adolescents was a challenge, but I very much enjoyed it.

I loved the monastic liturgy — particularly the concelebrated Masses and the weekly Benedictions

performed with positively mediaeval, yet timeless, grace and solemnity: the magnificent hymn singing

(so many lovely Welsh tunes with English words); and who could forget 'For all the Saints' sung with

verve and volume?

So why did I leave? Three years and seven months after I took over Hedley House the headmaster

announced, at a December staff meeting, that the 'Hedley House Experiment' was to be considered and

voted upon during the Christmas holidays. No doubt I was tired at the end of the Michaelmas term —

trying to run my home in Bath by remote control, visiting it only once a fornight for a couple of hours,

and seeing so little of my family was quite a strain. I had been offered several other jobs over the years

but none had appealed to me as much as Belmont and Hedley. Now, however, I thought that the

controversial, sometimes uneasy, experiment would end and therefore advised Gabbitas and Thring,

and other interested people, that I would shortly be free.

Presumably this created a psychological break. At all events, I was genuinely surprised when the

headmaster telephoned to "congratulate" me because, "by a large majority" the Hedley Experiment

had been voted "a success and a permanency". The Head of English had made an impressive speech

praising all the good that we had done to Belmont. Somehow that meant even more to me than praise

(of both my teaching and Hedley House), delivered by the Head of Her Majesty's Inspectorate team at a

recent visitation. It had not been an easy job and the support of colleagues is a great fillip.

Nevertheless, I told Father Mark that this was my 'Nunc Dimittis'; my family was insisting that I

accepted another post nearer home. I stayed on for a further fourteen months before becoming the

Director, County of Avon Branch of the Red Cross. Belmont had given me exactly five years of

wonderful experience. You might think that directing over 2,000 doctors, nurses, ambulance drivers,

welfare officers and others was not anything like running Hedley and teaching boys: but, of course,

personnel management and improving one's administrative skills builds on previous experience —

including mistakes; I still made mistakes but different ones! Belmont had prepared me for long hours; it

also accustomed me to working late at night which proved very useful.

WHAT OF THE GIRLS' CAREERS? Almost sixty girls passed through Hedley in my time: (1971 - 6). I

was the longest serving housemistress by three years. Many of the Old Girls have been awarded degrees,

scholarships and diplomas; Rose Kerr, M.A., with First Class Honours, is Keeper of the Fine Arts (Far

Eastern) Dept. of the Victoria and Albert Museum; Gemma Reidy is taking a post-graduate degree to

become a Master of Existential and Phenomenological Psychology. Caroline Robertson who is

Manager of the West Midlands Finance Division of the Bank of Scotland, was recently presented with

the First "Achievement Award for Managers" by the Managing Directors of her Bank — and that

before an audience of 1,400. Sara Scanlon (nee Lethbridge) B.A., is a Job Creation Consultant in

Swindon; Ann Cafferty a Departmental Manager of Harvey Nichols; Angela Pinnington a Divisional

Manager of a pharmaceutical firm. Philippa Walker is a Doctor, several others are Nurses and

Teachers, Accountants, a Radiographer, Veterinary Nurse and so on. There are, thank goodness, also

those who are successful wives and mothers handing on the faith (and some ideas they learnt at

Belmont?) to their families.

It is a joy to see any of them at my home or elsewhere and I treasure the memory of such introductions

as:

"No, this isn't the one I brought last time I came. He's a different one: the one I'm going to marry!" and

"Mrs. King — you won't recognise me — I've gone blonde! I'm bringing... to meet you. You won't tell

him what I did at Belmont, will you?"

I am also delighted when monks and former colleagues drop in when passing. Belmont is very much a

FAMILY: it keeps in touch with former pupils and staff, and looks beyond our favourable

circumstances to the marginalised, the dejected and disabled in this country; turning to us, also, for the

support of Belmont's missionary work in Africa and Peru.

In April 19761 left a full Hedley House with a waiting list. Two years later all the boarders had gone. It is

good to know that there are day girls because I feel that Belmont has so much to offer and to share. I feel

greatly honoured to have been asked to give an address and to present the prizes at the Speech Day of

1986 and, subsequently, to have been made an Honorary Member of the Belmont Association. It seems

the final accolade — to be invited to write an article for the magazine about Hedley. I apologise for so

many personal references but Hedley is inseparable from my life; this is part of the Belmont magic!

Once I started to scribble the piece became a pamphlet and for this, too, I apologise: there are so many

memories that I recall with affection or with affectionate exasperation!

The title "Hedley Kaleidoscope" should allow the Editor scope for cutting — but blame him, and not

me, if you or your favourite nostalgic memory has been distorted or left out.

If we don't meet again in this life I shall hope to see you as "through gates of pearl streams in the

countless host". If you don't know where that quotation comes from its a disgrace!

Pauline King, M.B.E., S.R.N.

1988